Inference from phylogeography and molecular epidemiology of Lassa virus is limited by sampling and sequencing bias in endemic regions.

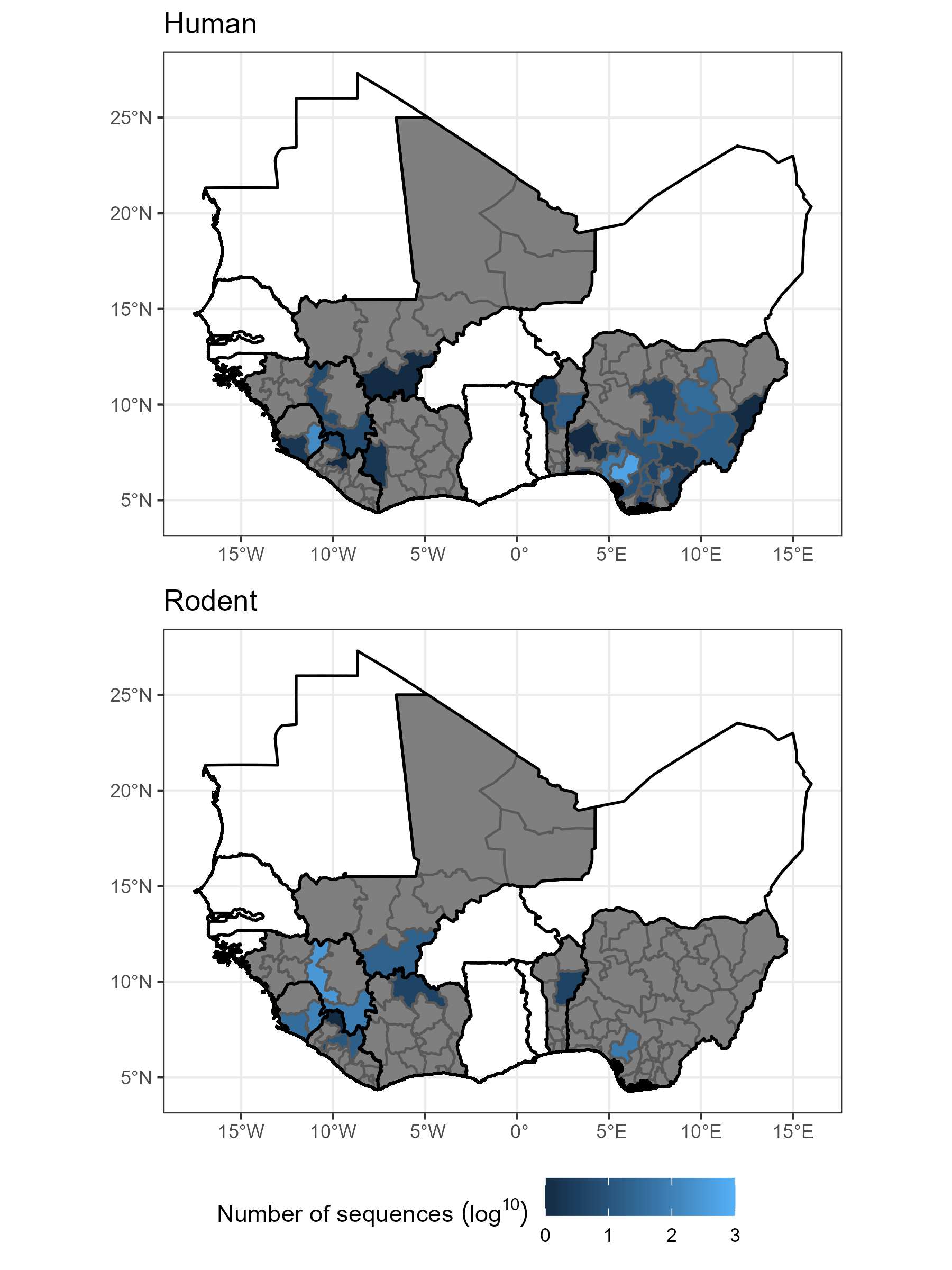

Lassa fever (LF) is a potentially lethal viral haemorrhagic infection of humans caused by Lassa mammarenavirus (LASV). It is an important endemic zoonotic disease in West Africa with growing evidence for increasing frequency and sizes of outbreaks. Phylogeographic and molecular epidemiology methods have projected expansion of the Lassa fever endemic zone in the context of future global change. The Natal multimammate mouse (Mastomys natalensis) is the predominant LASV reservoir, with few studies investigating the role of other animal species. To explore host sequencing biases, all LASV nucleotide sequences and associated metadata available on GenBank (n = 2,298) were retrieved. Most data originated from Nigeria (54%), Guinea (20%) and Sierra Leone (14%). Data from non-human hosts (n = 703) were limited and only 69 sequences encompassed complete genes. We found a strong positive correlation between the number of confirmed human cases and sequences at the country level (r = 0.93 (95% Confidence Interval = 0.71 - 0.98), p < 0.001) but no correlation exists between confirmed cases and the number of available rodent sequences (r = -0.019 (95% C.I. -0.71 - 0.69), p = 0.96). Spatial modelling of sequencing effort highlighted current biases in locations of available sequences, with increased sequencing effort observed in Southern Guinea and Southern Nigeria. Phylogenetic analyses showed geographic clustering of LASV lineages, suggestive of isolated events of human-to-rodent transmission and the emergence of currently circulating strains of LASV from the year 1498 in Nigeria. Overall, the current study highlights significant geographic limitations in LASV surveillance, particularly, in non-human hosts. Further investigation of the non-human reservoir of LASV, alongside expanded surveillance, are required for precise characterisation of the emergence and dispersal of LASV. Accurate surveillance of LASV circulation in non-human hosts is vital to guide early detection and initiation of public health interventions for future Lassa fever outbreaks.

This project developed from Hayley Free’s MSc project based at the Royal Veterinary College. We obtained GenBank data on Lassa mammarenavirus sequences to investigate the phylogeny of these samples and to understand how biased these may be as a dataset. We were particularly interested in how many human derived sequences were obtained from the different regions with known outbreaks of human disease and comparing this to the coverage of rodent derived sequences.

We found that there is important spatial heterogeneity in where samples are obtained from that does not match the known distribution of rodent infections and human cases. For example, most human sequences came from Nigeria and Eastern Sierra Leone. While most rodent sequences came from Guinea and Eastern Sierra Leone with very few from Nigeria. This disparity likely has an important impact on the inference that can be drawn from phylogeographic studies of Lassa mammarenavirus.

This work has been published as Current sampling and sequencing biases of Lassa mammarenavirus limit inference from phylogeography and molecular epidemiology in Lassa fever endemic regions in PLOS Global Public Health and is available under open-access on the journal website.

Citation

@online{free2022,

author = {Free, Hayley and Simons, David and Honeyborne, Isobella and

Elton, Linzy and Haider, Najmul and Ansumana, Rashid and Kock,

Richard and Ntoumi, Francine and Zumla, Alimuddin and D McHugh,

Timothy and Arruda, Liã},

title = {Inference from Phylogeography and Molecular Epidemiology of

{Lassa} Virus Is Limited by Sampling and Sequencing Bias in Endemic

Regions.},

date = {2022-10-01},

langid = {en},

abstract = {Lassa fever (LF) is a potentially lethal viral

haemorrhagic infection of humans caused by *Lassa mammarenavirus*

(LASV). It is an important endemic zoonotic disease in West Africa

with growing evidence for increasing frequency and sizes of

outbreaks. Phylogeographic and molecular epidemiology methods have

projected expansion of the Lassa fever endemic zone in the context

of future global change. The Natal multimammate mouse (*Mastomys

natalensis*) is the predominant LASV reservoir, with few studies

investigating the role of other animal species. To explore host

sequencing biases, all LASV nucleotide sequences and associated

metadata available on GenBank (n = 2,298) were retrieved. Most data

originated from Nigeria (54\%), Guinea (20\%) and Sierra Leone

(14\%). Data from non-human hosts (n = 703) were limited and only 69

sequences encompassed complete genes. We found a strong positive

correlation between the number of confirmed human cases and

sequences at the country level (r = 0.93 (95\% Confidence Interval =

0.71 - 0.98), *p* \textless{} 0.001) but no correlation exists

between confirmed cases and the number of available rodent sequences

(r = -0.019 (95\% C.I. -0.71 - 0.69), *p* = 0.96). Spatial modelling

of sequencing effort highlighted current biases in locations of

available sequences, with increased sequencing effort observed in

Southern Guinea and Southern Nigeria. Phylogenetic analyses showed

geographic clustering of LASV lineages, suggestive of isolated

events of human-to-rodent transmission and the emergence of

currently circulating strains of LASV from the year 1498 in Nigeria.

Overall, the current study highlights significant geographic

limitations in LASV surveillance, particularly, in non-human hosts.

Further investigation of the non-human reservoir of LASV, alongside

expanded surveillance, are required for precise characterisation of

the emergence and dispersal of LASV. Accurate surveillance of LASV

circulation in non-human hosts is vital to guide early detection and

initiation of public health interventions for future Lassa fever

outbreaks.}

}